How Mentor Texts Support Writers

In evidence-based writing instruction like Jump Into Writing! and Patterns of Power, you'll often run across the phrase "mentor texts." What does it mean—and why does it matter?

What Is a Mentor Text?

First and foremost, mentor texts are pieces of literature—usually picture books and chapter books but also sometimes essays, poems, short stories, plays, news articles, song lyrics. . . generally anything like what you want to write.

Lynne Dorfman, co-author of Zaner-Bloser's Jump Into Writing! curriculum and many professional texts for teachers, explains that mentor texts are pieces of writing that both student and teacher can return to over and over again for many different purposes.

"Mentor texts are like a deep well that you can keep returning to and cupping up water from it."

—Lynne Dorfman

In short, mentor texts are like the people who are mentors in our lives. Sometimes we go to them with a sense of what we can learn from them, and sometimes we discover something we didn’t even know we needed.

Mentor texts are models of excellent writing that we can study and imitate. Often mentor texts help writers move forward and take risks by trying out new strategies in their writing.

While literature in any genre that you want to write—and want students to write—can serve as a mentor text, there are some characteristics that help educators choose mentor texts for the classroom. Most importantly, classroom mentor texts must be accessible and relatable for all students while allowing students to see reflections of themselves. Other hallmarks include:

- rich vocabulary

- focused plots

- intentional brevity

- hearty visuals

Frequently, core and supplemental writing resources for the classroom include pre-selected mentor texts. This reduces teacher prep time and provides concrete examples of how mentor texts can be used in lessons. Many teachers enjoy adding mentor texts to the collection they use in class by noticing what texts resonate most with students each year and bringing those favorites into the curriculum when relevant.

Lynne reminds us, “Like a pair of old blue jeans, mentor texts are comfortable, reliable, and something you return to over and over.”

Why Are Mentor Texts Important for Writers?

If you’re a seasoned musician, you may have noticed that you hear a piece of music differently than non-musicians. You might notice and think deeply about the range of notes, changes in tempo, when specific instruments enter an arrangement, what is repeated, and what sounds unique, for example. The same is true for a carpenter looking at a piece of wood furniture, a potter examining ceramic vases, a great cook eating a meal someone else prepared, an accomplished athlete watching a game. . . we tend to notice and think deeply about how things we’re familiar with are crafted. This is what mentor texts help students do with writing. We can study the author’s craft moves in the text.

We can teach students to notice the passages—a sentence, phrase, or single word choice perhaps—that capture their attention in a mentor text. We can teach them to linger and think about why the author did that instead of a million other things they could have chosen instead. Why did the author use these words. . . in this order. . . right here? What is repeated and why? Why is some text BIGGER or bolded? What’s that punctuation with the three dots. . . ? This is how we teach students to be curious about writing and to notice how authors convey meaning.

Stacey Shubitz, co-author of Jump Into Writing! with Lynne, explains, “Mentor texts empower students to become independent. . . because they won’t always have you as their writing teacher.”

“Mentor texts empower students to become independent. . . because they won’t always have you as their writing teacher.”

—Stacey Shubitz

When we teach students to notice another author’s craft, to think about why the author made that choice, and then to consider how they might use the same craft strategy in a piece of their own writing, we empower them to think—and write—like seasoned authors.

How Are Mentor Texts Used in Teaching Writing?

Read-Alouds

Mentor texts can be used in many ways to teach writing, but students should encounter the text in a read-aloud before it appears in a lesson. They should experience it as a listener, letting the words wash over them so they can delight in the story or the information being offered.

Students need to hear and appreciate the wonderful words, their rhythm, the story, the characters, and the message. They need time to respond to it from the heart, as a reader, before returning to the text to examine it through the eyes of a writer.

It is fine—and often helpful—if some students have read or heard the mentor text before it is read aloud in class, but no matter how well known it is, the mentor text should be read aloud again before being declared a mentor text for the whole class to use in writing.

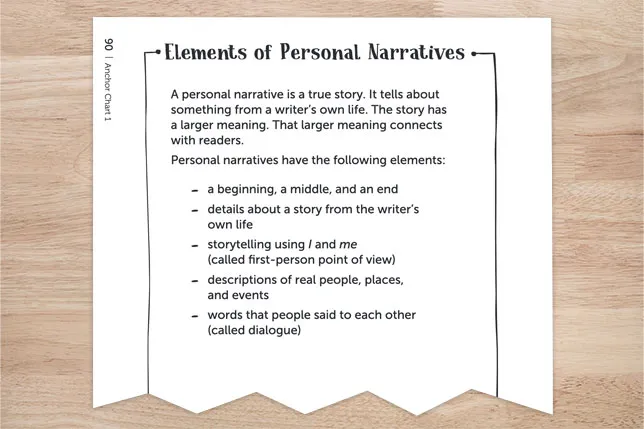

Immersion

At the start of a writing unit, mentor texts can help students discover the characteristics of the genre they’re going to write. A class starting a personal narrative unit, for example, might look at two mentor texts: Happy Like Soccer by Maribeth Boelts and Lauren Castillo and The Wednesday Surprise by Eve Bunting and Donald Carrick. One thing students will likely notice is that both stories are written in first-person voice—that is, the authors are telling stories that happened to them.

Craft Moves

Once students are working on their own drafts, each day’s minilesson can help them notice one craft move that published authors make. A craft move is something the author of a mentor text did that students can try in their writing as well.

For example, you can teach students the craft move of adding dialogue to a story to reveal important information about characters or move a plot along. You simply start by pointing out the dialogue in a mentor text and thinking with students about why that dialogue appears where it does in the story. What does the dialogue do for the story and why is it important?

In this way, you continue to model how students can use mentor texts to inform their own emerging drafts. Sometimes students drive the discoveries by noticing things about the mentor text and asking questions about them, and sometimes teachers drive discoveries by pointing out things authors did in mentor texts that students can do too.

Conferring

Many teachers have a mentor text or two on hand when conferring one-on-one with student writers. Then, if a student states they’re struggling to figure out how to accomplish something specific in their draft, you can look together at how the author of a mentor text solved a similar problem.

If a student doesn’t offer a specific question or problem they’re trying to solve, you can suggest that they try a craft move visible in the mentor text. This is a great way to differentiate instruction to meet all students’ needs. You can challenge a few students to try a more sophisticated craft strategy while inviting others to notice how the author uses a capital letter at the start of each sentence, for example.

Grammar

Teachers can dedicate ten minutes daily to specific grammar instruction using mentor texts as well. Using the process described in the Patterns of Power family of resources, students look closely at well-crafted sentences from books they know. Over the course of several days, students describe what they notice about the sentence, compare and contrast it with another sentence, try the observed strategy, apply the pattern to new sentences, and explore how editing changes meaning or effect.

While this focused grammar study should take place separate from the minilesson and conferring that happens in the daily writing time, the structure—and learning—certainly transfers between segments of the day! What a student observes and learns in the focused grammar study can be applied to their draft-in-progress.

Discover More About Mentor Texts

Learn more about the important roles that mentor texts can play in a writing curriculum and get acquainted with some exemplary mentor texts in specific genres and grade levels by exploring the Jump Into Writing! program.

You May Also Like