The Simple View of Writing: Building Automaticity for Success

Maybe you’ve heard that handwriting skills improve the quality of students' compositions. To understand why—and what it means in terms of what we teach in school—we can look at a theoretical model called The Simple View of Writing.

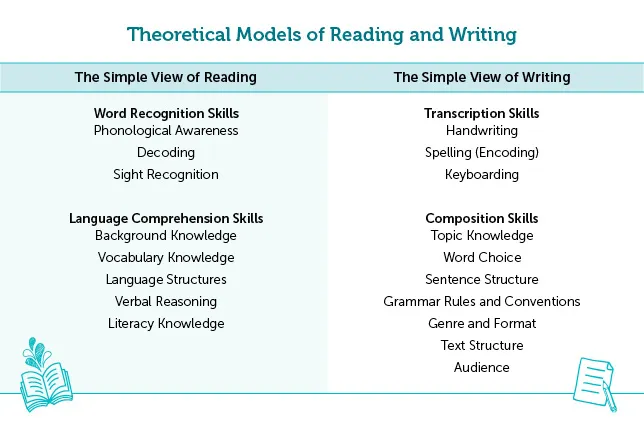

Simple Views of Reading and Writing

If you’re already familiar with the science of reading, you likely know The Simple View of Reading and Scarborough’s Reading Rope. These two theoretical models help us understand what students need to learn to become skillful readers. For example, both models tell us that students need word recognition skills and language comprehension skills for their reading to be strong. Scarborough’s Reading Rope also helps us visualize the value of automaticity, as word recognition skills happen more rapidly, accurately, and with little conscious effort over time.

National literacy consultant Amy Siracusano notes that The Simple View of Writing gives us similar information about what students need to learn to become skillful writers. Just as word recognition skills and language comprehension skills are equally important in reading, transcription skills and composition skills are equally important in writing. These overarching skills in reading and writing even contain similar subskills as you can see below.

In the same way that word recognition skills become increasingly automatic over time in Scarborough’s Reading Rope, transcription skills become increasingly automatic over time in writing. Language comprehension skills become increasingly strategic over time in reading, and composition skills become increasingly strategic over time in writing.

Implications for Teaching Writing

What does The Simple View of Writing mean for writing teachers, literacy coaches, and ELA instruction in elementary school? Siracusano reminds us that both transcription and composition are equally important. Just as in the Simple View of Reading, strength in one skill set can never compensate for weakness in the other.

Additionally, just as the word recognition skills required for reading must be explicitly taught, the transcription skills for writing must be explicitly taught as well. That means handwriting and spelling instruction—and at the right time, keyboarding instruction—must be part of the school day alongside explicit composition instruction.

In this article, we dive deeper into what research tells us that explicit handwriting instruction should include. Before the details, however, we'll start with perhaps the best news of all for busy educators: "explicit" handwriting instruction doesn't mean time consuming. Short bursts of 10–15 minutes per day, several days a week, have positive impact.

Handwriting Across Grade Levels

The desired outcome of teaching transcription skills in writing—like the goal of teaching decoding skills in reading—is automaticity. Students must be able to translate their thinking into written text quickly and legibly, so others can read and understand it.

Students must be able to print letters and spell words without looking at models—without even consciously thinking about printing and spelling. This enables students to write more complex pieces of text over time, to focus on language, nuance, and ideas as they’re writing. This process takes many years of practice to develop.

Grades K–1

Students in the U.S. typically start learning to form manuscript letters in kindergarten and first grade, and they should continue that work for a minimum of two years because that's how long research says it takes to automatize handwriting. They'll also learn punctuation marks. Many state standards require end marks for sentences by the completion of first grade. Students at these ages can also begin working on spatial organization, such as how to use margins and lines on paper.

Grades 2–3

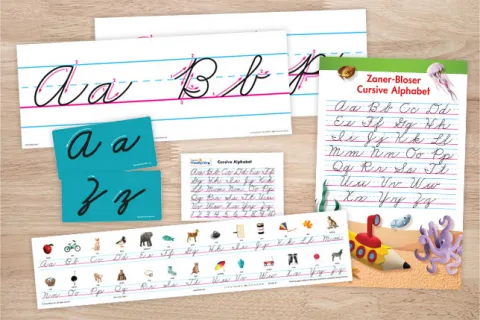

In second and third grade, students continue working toward automatizing manuscript letters while simultaneously moving into cursive letter formation. Not only are there new letter representations to learn but also new spatial organization skills (paragraphing, for example) and spelling patterns to learn. All of these transcription subskills are growing in complexity while also becoming more automatic due to continued practice.

Grades 4–5

Remember that research tells us it takes two years to automatize handwriting, so if students start cursive in second grade, they'll need to continue practicing it through at least fourth grade. If cursive is taught in third grade, students will need to practice through at least fifth grade.

Meanwhile, all the work of other subskills in transcription continue becoming increasingly complex—paragraph breaks, quotation marks, punctuation in the middle of sentences, spelling, morphology, etc.—and must be integrated with what students are simultaneously learning about handwriting.

Keyboarding

Sometimes keyboarding instruction begins as early as second and third grade, and students are asked to type extended responses on assignments. Siracusano describes this as a mistake in most instances. Students should not be asked to write extended pieces of text using a keyboard until they can type a minimum of twenty correct words per minute.

If students haven't automatized their handwriting and we ask them to transition from using one hand—producing writing in manuscript—to requiring two hands and memorizing where letters are on a keyboard, the demand is simply too much for their working memory to handle. The transcription skills require too much of their focus, so students struggle to articulate their thinking simultaneously.

Keyboarding is an important transcription skill because it is a real, culturally valid mode of writing letters on a page or screen to convey ideas. Keyboarding should not be used as an alternative to handwriting, however. It is an additional skill that must be learned, even—or perhaps especially—for students who are struggling with handwriting practice.

Effective Handwriting Instruction

Fortunately, research tells us a lot about effective handwriting instruction. As you've already read, just 10–15 minutes of explicit handwriting instruction per day several days per week will help students develop the required automaticity in as few as two years per mode. Here are five research-based ways we can make that instructional time productive and engaging.

Motor Activities

Writing requires students to move what they know about letters from a storage center in their brains to three fingers in their dominant writing hand. That's not only a linguistic task but a motor task as well. A variety of motor activities will support students in this work.In today's classrooms, fewer children have routine experience playing with modeling clay or pulling blocks apart, so they may be missing the muscle mass in their hands that handwriting requires. Working with them on picking up small beads or coins with their thumb and pointer can help with handwriting tasks including holding the pencil correctly.

Alphabet Recall

Once students know the alphabet in order, we can invite them to recall the letters starting somewhere other than "A." You might say, "What are the next three letters after the letter 'B'? Write them."Or "What are the three letters before 'M'? Write them." This helps students cement those letters and letter sequences in their long-term memory.

You likely use a similar strategy in math class, teaching students to count on starting from a number other than 1. This task with letters of the alphabet is equally valuable in ELA but often overlooked.

Handwriting Language

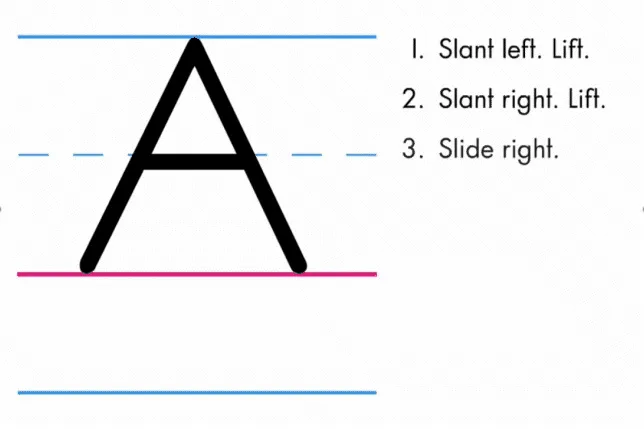

Students should hear, read, and use language that describes the strokes required to make writing on paper. We can model the language as we model the handwriting itself, describing our movements as we go.We can choose handwriting materials that include arrows and numbers to tell students where to start, where to finish, and how to move. We can ensure our materials teach students how to write uppercase and lowercase letters, punctuation, and the numbers in our number system.

Pencil Position

When building the foundation for handwriting automaticity, we want to teach students how to hold their pencil the right way to set them on a path toward speed and legibility. Simple, explicit instruction using specific vocabulary helps here too. Watch the short tutorial from Zaner-Bloser Handwriting to see for yourself!

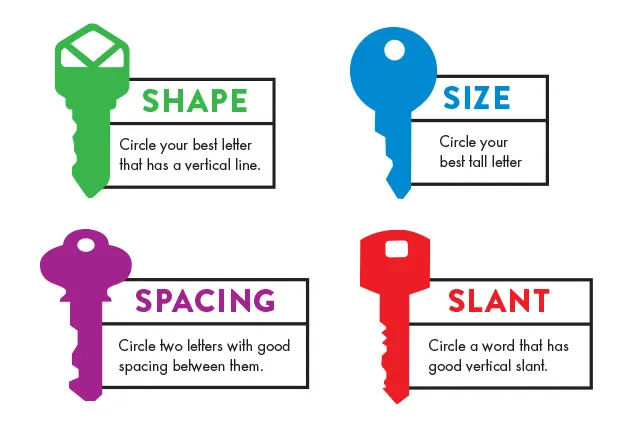

Evaluation Tools

Last but not least, we want to give students evaluation tools that help them understand what success looks like. We can use these tools not only when we evaluate student work but also encourage students to self-evaluate using the same criteria. Zaner-Bloser Handwriting, for example, features four simple Keys to Legibility: size, shape, spacing, and slant.

Transcription: The Missing Piece of the Writing Process

You may be thinking of the writing process you learned in school—perhaps the same one you've been teaching for years—and wondering how The Simple View of Writing fits.

The writing process we are most accustomed to seeing in classrooms is focused on content. Prewriting, drafting, responding, revising, editing, and publishing are indeed steps that skilled writers make when composing. But the model of that process was developed in consultation with skilled writers who already had mastered transcription skills. Handwriting, keyboarding, spelling, punctuation, and spatial organization were automatic for those writers, so they were free to focus on the higher-level strategy of composition.

If we teach writing focused solely on content and ignore those transcription skills, we're missing a big piece of the puzzle, and our students are going to struggle. If we help them develop transcription skills and composition skills, they'll have the automaticity and strategy they need to write skillfully.

You May Also Like