How Kids Learn to Spell Words

Spelling is a writing skill, and it’s a powerful reading skill too. Examining how students’ spelling skills develop over time reveals how their thinking about words progresses.

When students study phonics, they learn to connect letters and letter patterns to specific sounds and blend them together to decode words. This is a critical component of learning to read.

Spelling is the inverse of phonics. It requires students to encode words, segmenting the sounds they hear into letters and letter patterns they can write on a page.

Explicit phonics instruction and explicit spelling instruction improve students' abilities to read—and write. When students learn to spell words, they analyze and remember the letters, sounds, and meanings that go together. They pay closer attention to individual sounds, or phonemes, and how they’re represented in print. This makes reading and writing faster and more accurate, increasing automaticity and fluency.

The roles decoding and encoding play in reading and writing are visible in researchers’ theoretical models. The science of reading includes two models that explain what students need to become skillful readers of text. Both The Simple View of Reading and Scarborough’s Reading Rope emphasize the importance of decoding. The Simple View of Writing provides a parallel model that describes what students need to know to become skillful writers. It explains the importance of transcription skills including spelling and handwriting.

Spelling Stages

As kids explore and learn about texts, language, and words, their spelling skills progress developmentally through distinct stages. Dr. Richard Gentry, author of Spelling Connections: A Word Study Approach, describes five stages detailed below: precommunicative, semiphonetic, phonetic, transitional, and correct.

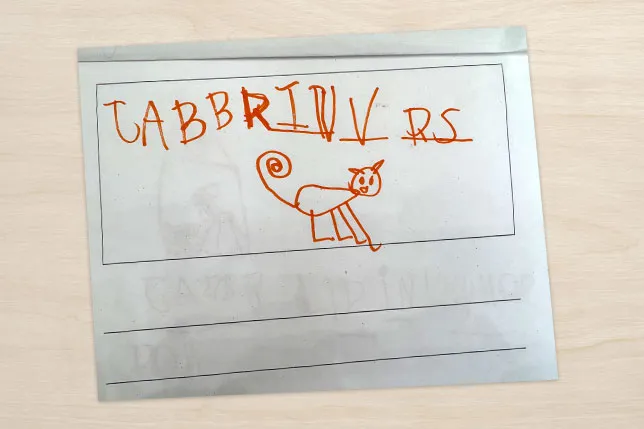

Random Letters (Precommunicative Stage)

The first stage of encoding doesn't look much like spelling. Students in this stage know some letters and understand that letters make up the text on a page, but they don’t yet have letters mapped to specific sounds. They don’t group letters in meaningful ways on the page. They may not understand that letters are written and read from left to right across the page.

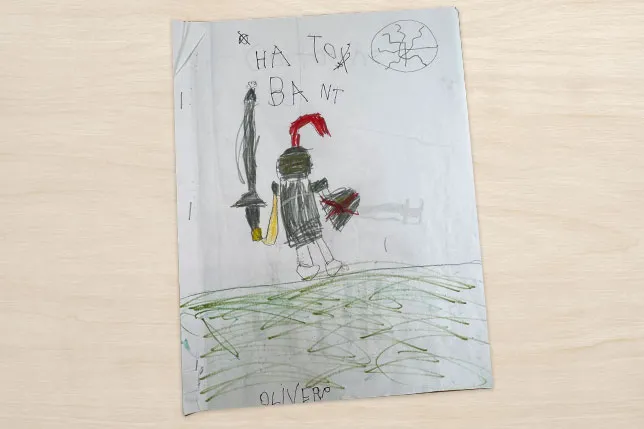

First and Last Letters, Single Letters (Semiphonetic Stage)

As students develop understanding of letter–sound correspondence, they spell with rudimentary logic, perhaps using single letters (u for you and b for be), focusing on beginning and ending sounds, and/or using consonants but not vowels.

Invented Spelling (Phonetic and Transitional Stages)

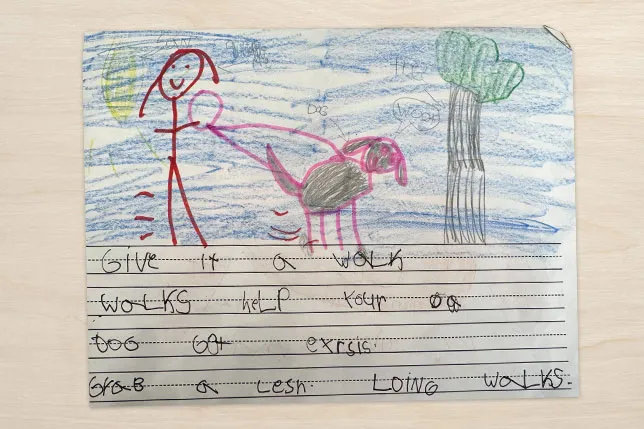

In the phonetic stage, students write a letter or group of letters to correspond to each sound in words. Words are often not spelled correctly, but there is clear phonetic logic in students’ spelling decisions. Writing can be deciphered by others.

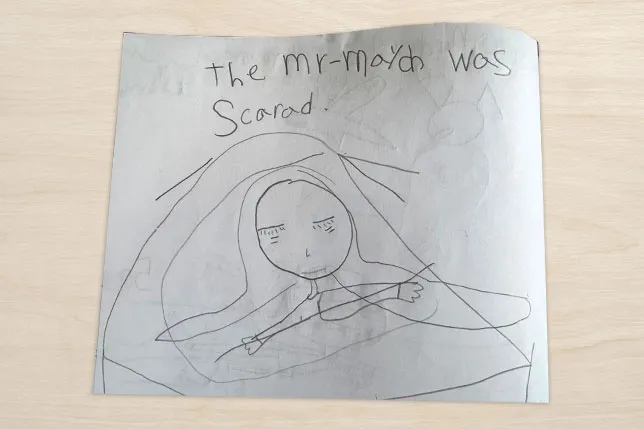

As students encounter more sophisticated letter patterns and words they recognize by sight, a transitional stage emerges. Here students rely less on phonetic interpretation alone, perhaps overapplying knowledge of letter patterns (for example, igh for a long i sound). In the example below, a student who knows the word may applies that knowledge when writing the unfamiliar word mermaid.

The progression from one stage of spelling to the next is gradual, and a writing sample may have characteristics of two different stages at the same time.

Invented spelling is evident—and should be encouraged—in written work by kindergarten, first-grade, and second-grade students. Research indicates that second-grade students use invented spelling for nearly one third of the words they write. Even as adults, we may occasionally use invented spelling for unfamiliar words.

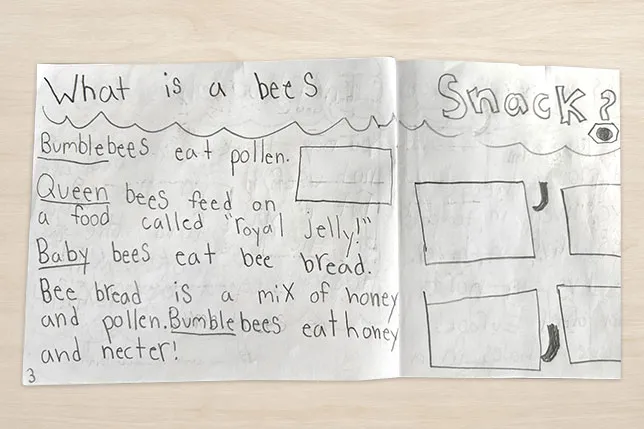

Conventional Spelling (Correct Stage)

In the final stage of spelling, understanding of the English word system is evident. Most words are spelled correctly. The speller knows when a word is not spelled correctly and can use available resources to make necessary corrections.

Research indicates that students can typically identify any misspelled words in a text by fourth grade, even if they are unsure how to correct them.

Gentry's stages describe specific encoding skills, but reading researcher Linnea Ehri has described similar stages specific to decoding (pre-alphabetic, partial alphabetic, full alphabetic, consolidated alphabetic, and automatic). The progression described by both researchers emphasizes the importance of understanding the relationship between letters and sounds.

How to Teach Spelling

Since spelling is a critical component of both reading and writing that develops progressively over time, how might we support student growth? We can look again to the science of reading and The Simple View of Writing for an answer.

The science of reading tells us that word recognition skills including phonics must be explicitly taught. The Simple View of Writing indicates that transcription skills including spelling must be explicitly taught as well.

Effective spelling instruction helps students move from one developmental stage to the next. In early elementary school, phonics instruction can aid reading and spelling if students are given frequent and meaningful writing opportunities to practice both encoding and decoding text.

After basic phonics in the early grades, explicit instruction continues with broader exploration of words and spelling patterns. Morphology (the study of word parts like prefixes, suffixes, Greek and Latin roots), syllable types and orthographic mapping, advanced phonograms (letter combinations such as -eigh and -tion in weight and station), and vocabulary instruction improve spelling skills, which cascades further into reading and writing.

Characteristics of Good Spelling Instruction

Research reveals four key elements of effective spelling instruction.

- Reduced Focus on “Right” Spelling

It is important that early writing activities do not overemphasize spelling accuracy. As described in the developmental stages above, many spelling “errors” are signs of a growing understanding of words—and can be helpful in assessing what concepts a child has mastered as well as what to teach next.

- Carefully Curated Spelling Lists

Spelling should not require rote memorization of words, and word lists should be intentionally constructed—organized by spelling patterns and reflective of vocabulary that frequently appears in age-appropriate reading and writing.

- Efficient and Personalized Word Study

A pretest–study–test model helps students connect what they already know about spelling to new words. Students can self-check their pretests to identify the words they don’t know yet and need to study. This model fosters a deep understanding of spelling rather than rote memorization that doesn’t stick.

- Collaboration and Curiosity Encouraged!

Spelling games, word sorts, and a culture of curiosity for words help motivate students in spelling as well as writing more broadly. It’s fun to think about words!

A Word Study Approach

Ready to improve students’ reading and writing skills with explicit, research-based spelling instruction? Spelling Connections: A Word Study Approach offers students in grades 1–6 the right words and the right spelling strategies at the right time—in just 15 minutes per day.

You May Also Like